Tu carrito está vacío

Free Shipping on orders $499+

Proudly Made In Massachusetts! ![]()

Exploring the World of Digital Art for your Samsung Frame TV

Art is always changing, thanks to new technologies, ideas, and societal changes. In the ever-changing landscape of digital art, a new wave of artists is pushing the boundaries of what we consider "art."

From the pioneering work of Vera Molnár to Refik Anadol's immersive installations, digital art is no longer just something young people look at on their phones. It's a full-fledged movement that is challenging traditional notions of creativity and expression. It's disrupting what we think of as art, but because it's digital, it's available to be seen anywhere.

We'll dig into some of the most captivating digital artworks and look at their historical significance, technical innovations, and emotional impacts. This way, we can better understand the broader cultural and artistic shifts that are redefining how we engage with art in the digital age.

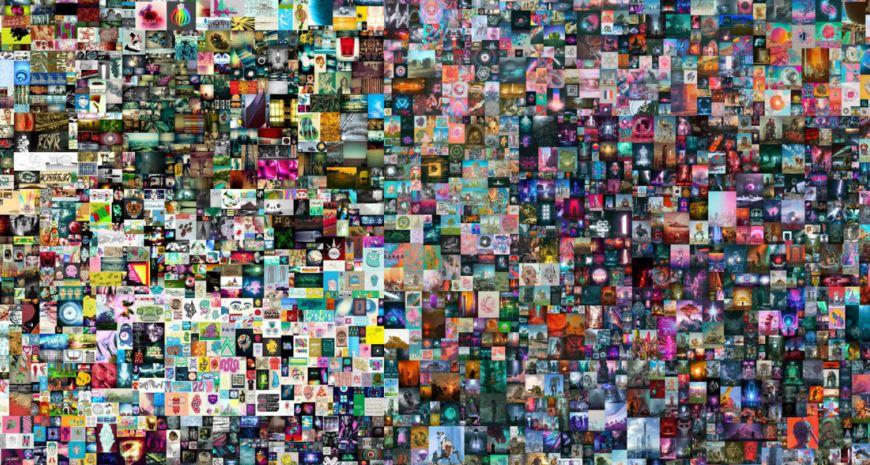

" Everydays: the First 5000 Days " made headlines in 2021 after Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) sold it as a non-fungible token (NFT) for $69.3 million. This made it the most expensive NFT to date and the third-most expensive piece of art ever sold by a living artist.

(Number one was Jasper Johns' "Flag," which he sold for $110 million in 2010; number two was Jeff Koons' "Rabbit," which he sold for $91 million in 2019.)

Beeple spent more than 13 years creating a single digital image every single day and then collecting all 5,000 of them into a single frame. Many of the images were created digitally, but many more of them were created by hand.

Beeple said he drew inspiration for the project from British artist Tom Judd. He started creating the daily project on May 1st, 2007, choosing some images from pop culture, creating others, and arranging them chronologically.

He featured characters from Star Wars, King Kong, Pokémon, and Toy Story, as well as other abstract, grotesque, or absurd images. And still others come from personal moments in Beeple's life.

The piece is "owned" by Vignesh Sundaresan, a Singapore-based crypto investor, who does not own the copyright to Everydays, only the right to display it in his digital museum — one of the drawbacks of digital art, I suppose. But you can explore a version of Everydays here or on your own Samsung Frame TV.

Vera Molnár, who was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1924, was one of the early pioneers in computer-generated art. Her first steps into algorithmic art began in 1959, with the concept of the "machine imaginaire," or imaginary machine. She used algorithms to guide her art before she ever accessed computers. In 1968, she learned programming languages like Fortran and BASIC to create graphic drawings on a plotter.

Her digital art is characterized by geometric shapes and algorithmic processes. But she didn't go completely digital: She combined digital and computer-based methods with traditional methods. And when she was 98 years old, she created her first NFT collection titled "Themes and Variations." This foray into NFTs cemented her status as one of the earliest pioneers in digital art.

Although she never pursued publicity and fame the way other famous artists have, Molnár was recognized as a Chevalier of Arts and Letters in France in 2007, and her work has been collected by several major museums.

Molnár passed away in December 2023 at 99 years of age, leaving a legacy as the "godmother of generative art."

Her collection, " (Des)Ordres" (some orders), is a word play on the French word "désordres" (disorders), which implies that there is an underlying logic contained within the disarray and chaos of the work — an apt idea, given that the work was created in 1974 on a computer plotter.

(Des)Ordres explores the connection between order and disorder. The work consists of concentric squares arranged in a grid but disrupted by randomness to create visual tension and vibrancy. These disruptions introduce an element of surprise, which animates the composition and reflects Molnár's interest in the balance between monotony and chaos.

Refik Anadol came to Los Angeles via Istanbul, Turkey, and has become a media artist merging the aesthetics of data visualization and AI arts. He mixes art, technology, science, and architecture to create mesmerizing digital art experiences that challenge our perception of space and time.

His collection of NFTs has generated more than $30 million in sales as of May 2024, which demonstrates the growing interest in and demand for digital art that goes beyond the boundaries of traditional artistic mediums.

Anadol's gorgeous and mind-bending collection, " Machine Hallucinations—Space: Metaverse ," features works inspired by his 2018 collaboration with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and his extensive research into the photographic history of space exploration. These aren't just photos of space: Imagine if a telescope and a lava lamp had a baby, and you peered at the deepest reaches of space through it.

Anadol's digital art often incorporates real-time data and machine learning to create mesmerizing images of color and light, like his " Winds of Yawanawá " collection, which merged weather data from the Yawanawá village in the Amazon rainforest with the work of young Yawanawá artists (and raised $3 million for the Yawanawá people).

Pascal Dombis is another digital artist from France who embraced algorithms and computer technology to create art. After earning an engineering degree in Lyon, he discovered digital art tools while studying at Tufts University, marking a pivotal shift from traditional painting to digital art.

His work is characterized by the excessive use of simple algorithmic rules, which results in complex visual forms. His works are marked by repetition and unpredictability, which can challenge the viewer's perceptions of space and time.

Dombis has created public art installations, including "Text(e)~Fil(e)s," a 252-meter-long floor ribbon at the Palais-Royal in Paris, and " End(less) ," which combines footage from thousands of movies where the words "The End" appeared in the final shot. He collected the footage from the earliest black and white films through the most recent Hollywood blockbusters, and movies from all over the world.

His art appears all over the world, including the Grand Palais in Paris, Itaú Cultural in São Paulo, the Venice Biennale. as well as Lujiazui Harbour City in Shanghai and the École nationale supérieure d'architecture in Strasbourg.

His piece, "THE END OF ART IS NOT THE END," is an interactive installation that, according to Dombis' website , "characterizes our current times: the end of world, the end of man, the end of civilization, the end of politics, the end of history, and, of course, the end of art." Dombis collected images by searching for "ends of...." and collected more than 20,000 images for this piece.

There's not much known about Carlos Ginzburg. He was born in 1946 in La Plata, Argentina, and is known for exploring the interplay between fractal art, chaos theory, and cultural complexity. He moved to Paris in 1972 — is France just a hotbed of digital and algorithmic art? — and created an art practice that spans painting, performance, and theoretical writing, blending scientific ideas with artistic expressions.

One of Ginzburg's most notable works is Homo Fractalus II (1999–2000), which is a collage on wood that measures 1 meter by 1.5 meters. If you've ever played with fractals on a computer, you understand the fascination with the recursive, repeating patterns that continue on into infinity, or at least as long as your patience will let you stare at the screen.

Ginzburg was heavily influenced by Edgar Morin's Tetralogy of Complexity, which delves into the interplay of order, disorder, interactions, and self-organization. He was also fueled in his pursuits by the advent of computers in the mid-20th century. Ginzburg incorporated these ideas and new technology into his art and created images like "Homo Fractalus II," using layered textures and fragmented imagery to evoke a sense of infinite depth and interconnectedness.

His creations have earned him a reputation as a pioneer in fractal art, and they have been exhibited internationally at institutions such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museo Nacional Reina Sofía in Madrid.

His work has expanded the boundaries of conceptual and digital art, as he uses fractals not only as mathematical constructs but as metaphors for human existence.

But then, don't we all?

German-born Manfred Mohr (1938) started using a computer in 1969 when he was interested in algorithmic art. He moved to Paris in 1963 — there's that French connection again! — and his interest in using computers slowly grew as he started exploring philosophy.

Mohr was originally a jazz musician and Abstract Expressionist painter, but he changed everything as he encountered the writings of Max Bense on information aesthetics, as well as the work of computer music composer Pierre Barbaud. These influences inspired him to explore the use of computers as creative tools.

As he told RightClickSave.com, "It was only when I got into the philosophy of Max Bense in the early 1960s that I understood that 'rational' thinking in art, as Bense proposed, could solve that problem. One has to create the logic of what one wants to do before one starts."

Mohr programmed his first computer-generated drawings in 1969 using the Fortran IV computer language. His early works focused on rhythm and repetition, translating his musical background and knowledge into visual compositions. My favorite work of his is Sphereless, which he created in 1972 with a plotter machine.

Mohr's work can be found in dozens of prestigious collections, including the Whitney Museum in New York, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Digital art is not a recent novelty; it's been around for decades, and it represents an evolution in the way we create, perceive, and interact with art. Artists like Beeple, Pascal Dombis, and Refik Anadol are at the forefront of the movement, building on the groundbreaking work of Vera Molnár, Carlos Ginzburg, and Manfred Mohr.

By embracing digital art, we create a world where technology and imagination converge to create visually stunning and intellectually stimulating experiences. We're not eschewing paint and canvas or marble and chisel. Computers are one more tool in the art world, letting people find new ways to express themselves and to reach art aficionados around the world. Digital art will no doubt play an increasingly important role in shaping the future of the art world, letting us see a future where creativity knows no bounds.